The following text is from Imbi Paju’s presentation for the Programme of European Commemoration 2014 in Berlin.

Although I have often participated in other types of seminars in many other countries, this is the first time that I have participated in a seminar supported by a government and which specifically addresses memory and how it affects people’s destinies.

Why is this connection so important?

My experience has shown me that museums, universities, film and literary festivals and theatrical performances are the venues through which most people discover and explore the traumas of wartime scars and remember wartime occupations – or their escape from them. These are the places where people can talk about the pain of loss and the political violence that caused it. Often politicians are less interested in the human suffering of ordinary people or in how memories of traumatic experiences affect them. For me it is very important that presidents, prime ministers, foreign ministers, defense ministers, and their staffs also explore these traumas through the haunting imagery of films, books and other media.

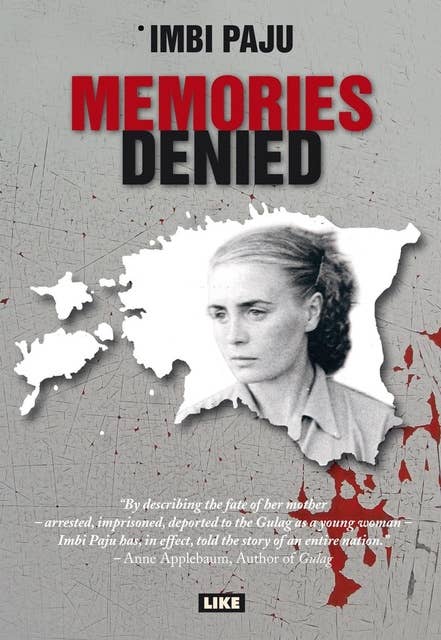

Understandably, a nation’s destiny – and that of its citizens – is shaped by political decisions. I have written about this in my book Memories Denied – which was published in German last October. My book investigates patterns of political violence, looking at them through the lens of historical fact, psychological impact and poetic language.

I felt it was important to find an emphatic language to retell history, which is, after all, the retelling of lives lived. I wanted to bring to the forefront an often hidden side of humanity, the violence which ordinary people endure in their everyday life. Where there is a history of political violence, there are also collaborators and victims; those who resist and those who remain silent. It was important for me to explore the patterns of violence that emerge from political systems so that people could see where we’ve been and where we might end up again if we are not aware of how violent modes develop. Such violence can completely remold our attitudes, our beliefs and our morals. Behind the violence there is always fear, but films and books – and other cultural media – can help people overcome their fear.

For Estonians, overcoming their fear requires looking back more than seventy years, to September 1939, when Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland. The fate suffered by Poland made the Estonians very anxious. My mother was 9 years old at the time. Her father had died 4 years earlier, because his health had been ill effected during the First World War. My maternal grandmother went on to raise her children alone, while keeping a small farm. In my book Memories Denied, as well as in my documentary film of the same name, I searched for the answers to what happened to my mother in Estonia during the political turmoil of the wartime years.

She was just 18 when the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, abducted her and her twin sister, along with hundreds of other Estonians. They were transported from Estonia thousands of kilometers east, to forced labour camps in Siberia.

Years later, as I was growing up, my mother had recurring nightmares. I remember hearing her cry out for help in her sleep. The whole family knew that she was dreaming that she was back in one of Stalin’s forced labor camps, from which she could not escape.

In the morning, she would be sitting at the table drinking coffee and looking out the window, her face was like stone. Finally, when Estonia became independent in 1991, and people dared to start talking, I learned more about what had happened to her and thousands of other Estonians.

Only after I finished making my documentary about her experiences from 70 years ago, did my mother´s nightmares disappear. She also regained her sense of smell, which she had lost at the age of 18, when she was deported to a forced labor camp in Soviet Russia.

My documentary included the stories of other women also sent to Siberia. I had a very hard time finding women courageous enough to talk about the physical violence and abuse that they were subjected to during interrogations. That is why I am especially grateful to my mother and her twin sister, who sadly passed away in September, for being the key women in my documentary. They gave me a wealth of information about their traumatic experiences. It took five long years, going through a very difficult emotional process, to create the film. Along the way I learned about the practices of the Soviet secret police: they routinely stripped victims naked and deprived them of sleep – to wear them down. By the year 2000 I was piecing together the full story of the Soviet occupation of my small country and the suffering of its people.

After the occupation of Estonia, the Soviet forces sent all the members of Estonia’s Parliament, as well as its ministers and police to Siberia, along with their families. The President was imprisoned and later sent to a psychiatric hospital. All military officers were shot. A total of 30 million books were destroyed. They were replaced by new Soviet history books and Soviet propaganda. The Soviets sought to destroy memory of Estonians and their sense of pride in their independent country.

Finnish psychoanalysts said that my work could be compared to psychoanalysis. And I was glad that my work was well received by ethnic Russians living in Estonia. Their parents had been sent to Estonia after it was occupied. (Under the Soviet Union, when a person graduated from school, he/she was sent to work somewhere. There was no such thing as self-employment.)

In both of my books and documentary films, I begin by examining the 1939 crisis and how the newspapers in various countries wrote about it. War was already in the air, but it hadn’t started yet. Every European nation was seeking ways to stay clear of it. Suddenly the solidarity of the European countries became markedly weaker. International newspapers followed the struggles of the Soviet Union’s leader, Stalin, to get England and France to negotiate a tripartite agreement. At the same time, he was also negotiating with Hitler, working to divide Europe. With the signing of the secret protocol of the Molotov-Rippentrop agreement, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany agreed to the division of Europe into two spheres of influence, giving Stalin control over the Baltic countries, Finland, and half of Poland.

After signing of the agreement, Soviet airplanes began to fly over the Baltic States. Under the threat of their attacks, the Baltic republics were pressured into signing an agreement that allowed Soviet military bases to be established in their territory. Events of the last few months have brought back fearful memories to many Estonians of those events of over seventy years ago.

Edward Lucas, Senior Editor at The Economist has written: “It is fashionable in some quarters to say that Estonians are neurotic about their history. Yet the real cause of neurosis is repression.” Estonia is a small country, with just 1.3 million inhabitants. The memory of the violence inflicted upon Estonia and the other Baltic republics is still so fresh that people here are quite anxious.

They are holding their breath and gathering signatures for petitions that ask France not to sell Mistral warships to Russia. Such a sale would endanger our security because we sit right on the Russian border. Our fear is not exaggerated. During the last few months, those of us who cross the Baltic Sea, traveling between Tallinn and Helsinki, have seen Russian submarines violating Estonian and Finnish maritime boundaries and endangering civilian marine traffic.

I have had my own fears while writing my books and making my documentaries. The kind of psychoanalytic historical research that I do requires quite a bit of courage, especially if one is a woman entering the predominantly male world of research historians. I have wanted to film interviews with the faces of the women turned away in order to protect them. It is extremely difficult, for example, to examine the subject of physical and sexual violence against women: rape was often used as a tool of warfare in Estonia and the Baltic states.

In Estonia and Finland, where all of my films and books were conceived, I’m surprised that that there is not a single woman working in the domain of the traditional researcher of history. In its official history, Finland is considered clever to have fought for its independence, while Estonia succumbed to Soviet pressures. In my opinion this is a very narrow, patriarchal view, which omits a discussion of why the countries bordering the Baltic Sea failed to work together when they had a chance to prevent the devastation that the war brought upon them.

It has been my experience that, where the citizenry of a country fails to discuss serious issues and share difficult experiences, that process is left to the next generation. I was acutely aware of this phenomena in October, when I made a series of presentations in five German cities, after my book Memories Denied was published there. I have also seen this in Taiwan, in Israel and elsewhere where my film has been shown. Life experiences are of universal importance for all people. Remembering them lessens fear and creates warmth and empathy between people and between different cultures. This is precisely how we become a part of these experiences.

I would like to recall what French-Jewish philosopher Simone Weil wrote: “No matter whether people have done good or evil, they want good done to them. This hope is holy within us.”

Keeping memory alive is only of use if it prevents the ignition of new wars. War is never a measure of life, but LIFE is a measure of life.

Source: UpNorth Magazine